The niftiest, runtime interned string tokens C++ can buy

While adding the static mesh packing system last week, I ended up creating a new key-value file format, which would be ingested by the packer as a map of strings to strings for specifying metadata on how to import a particular static mesh for packing. Given that the string keys were always of a predetermined value, I briefly mused over the idea of adding some kind of interned string functionality, and then launched into making it happen with reckless abandon instead of finishing up on the static mesh packer.

String interning is probably the most common terminology for this functionality, especially so in games programming. It refers to the process of taking any particular string and storing only one version of it, known as the “intern”. After which the system will use a more efficient representation of the intern for every copy of that exact, immutable string to reduce memory footprint and offset common, computationally expensive operations like string comparisons. Types and IDs are prime candidates for this treatment, outweighing the value of purely numerical hash values by providing a human readable format to work with.

It’s an incredibly useful and common feature for performance-critical software that will find this feature present in almost every commercial grade game engine’s default bag of tricks if not built directly into the language they’re written in. Epic’s Unreal Engine has the FName class, which will hash and store the string (along with a reference count) from its constructor, similar to Godot, which provides the StringName class. id Software’s Doom 3 engine takes the complexity a step further with idPoolStr, which can then be allocated with different string pools for different purposes, and then deallocated by entire pool as needed.

All this being said, one of my favourite usages of interned strings comes from my time working in feature animation and VFX with Pixar’s Universal Scene Description otherwise known as USD, with its TfToken class. Although the token class provides the same pool categorisation functionality as idPoolStr, and the automatic constructor interning of FName and StringName, the part I remember fondly was the easy-to-use registration macros it provided. It allowed for a single, static declaration-definition to be made and referenced across the project, avoiding user error and providing canonical values for systems to use as a standard currency. I should mention that some of these desirable attributes are reflected in the C++ API for Unreal’s GameplayTag, additionally boasting robust and well-tooled data driven tag registration faculties.

Reading through the implementation for TfToken, I was surprised at just how little went into the core functionality: a set of strings and some pointers. As it turns out, a pointer works just fine as a hash, and all we need to ensure in this process is that the value it points is never reallocated (at user space). The hash-mapped set class in the C++ standard library, std::unordered_set, makes for an ideal container for the tokens, where they will retain insertion order, and provide that insertion and search at an O(1) time complexity on average.

Below I have copied out an rough idea of the resulting Token class I created:

class Token

{

public:

Token() : tokenId(nullptr) {}

explicit Token(const char* name) : tokenId(FindTokenId(name)) {}

bool operator==(Token rhs) const { return tokenId == rhs.tokenId; }

// Note: < operator is required for comparison on some containers

bool operator<(Token rhs) const { return tokenId < rhs.tokenId; }

bool IsValid() const { return tokenId != nullptr; }

const char* tokenId;

};

std::unordered_set<String>& Token::GetGlobalTokenRegister()

{

static std::unordered_set<String> tokenRegister;

return tokenRegister;

}

Token Token::FindToken(const String& name)

{

return Token(FindTokenId(name));

}

Token Token::FindOrRegisterToken(const String& name)

{

if (name.IsEmpty()) return {};

std::unordered_set<String>& tokenRegister = GetGlobalTokenRegister();

auto it = tokenRegister.insert(name);

if (it.second) CC_LOG_INFO("Registered new token \"{}\"", name);

return Token(it.first->Str());

}

const char* Token::FindTokenId(const String& name)

{

const std::unordered_set<String>& tokenRegister = GetGlobalTokenRegister();

auto it = tokenRegister.find(name);

return it != tokenRegister.end() ? it->Str() : nullptr;

}As you can see, the secret sauce is in the global token register, which has a static lifetime and will be the home to all of our cannon strings. The token ID then serves both as the comparator, and a C-string for debug and display purposes using first byte of a Siege::String (similar to std::string), providing small string optimisation for lengths of less than 16 characters to avoid additional allocations. You may notice that I have purposefully disabled automatic registration on construction, as I prefer to perform registrations explicitly so I have better control over what strings become cannon.

With the functionality all there, we turn now to the registration functionality I wanted, for which we can break out the static registration pattern and wrap it all in a neat, little macro!

#define REGISTER_TOKEN(name) \

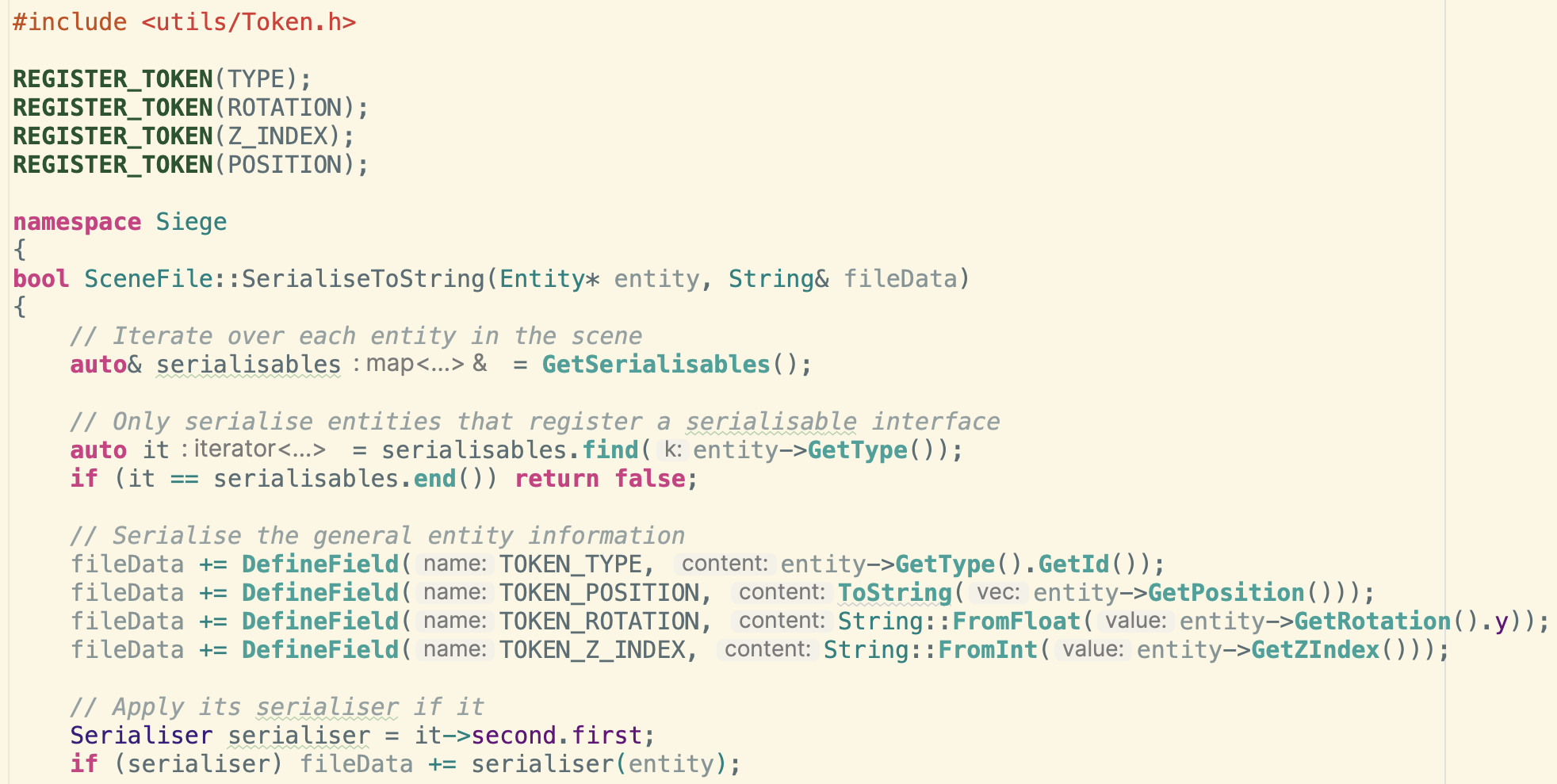

static const Token CONCAT_SYMBOL(TOKEN_, name)(Token::FindOrRegisterToken(TOSTRING(name)))In short, we are registering the token by name and then assigning it to a static field, all at initialisation time, so the field can be used across the program to reference the token as so:

#include <utils/token.h>

REGISTER_TOKEN(JointBindPath)

REGISTER_TOKEN(MaterialSlot)

void foo() {

Token djbp("JointBindPath");

if (TOKEN_JointBindPath == djbp)

{

CC_LOG_INFO("Now using token \"{}\"", TOKEN_JointBindPath);

}

if (TOKEN_JointBindPath != TOKEN_MaterialSlot)

{

CC_LOG_INFO("Tokens for \"{}\" and \"{}\" are not equal!", TOKEN_JointBindPath, TOKEN_MaterialSlot);

}

Token msi("MeshSkinIdx");

if (!msi) CC_LOG_INFO("Token for \"MeshSkinIdx\" is invalid!");

}

// OUTPUT:

// INFO at [main.cpp:24] Now using token "JointBindPath"

// INFO at [main.cpp:29] Tokens for "JointBindPath" and "MaterialSlot" are not equal!

// INFO at [main.cpp:33] Token for "MeshSkinIdx" is invalid!While I really enjoy using this simple implementation for tokens, there are two main drawbacks currently that I should note. The first of these being the inability to clear unused interned strings, and the second being thread safety.

As mentioned above, all three examples from major game engines employ reference counting to allow for the interning system to free any strings that are no longer in use by the engine. For me, this is not a concern at this time as the intended use cases range from material parameters to type IDs - it is not intended to be used as a general purpose currency in engine for strings. The second, and probably more relevant issue is thread safety, which like TfToken, can be achieved by placing a mutex or spin lock on access to the global token register. This is not necessary right now, as all accessing modules are run on the same thread, but this can be updated as needed in future.

Thanks again for stopping by to read up on my misadventures with Siege and I hope you got something out of this! If you’re interested in taking a look at Siege Engine’s source code, you can see the repo in action for yourself, or you can take a look at our GitHub to see any of our other open-source projects.