The fruits and folly of implementing an asset packing system in C++

Last weekend I found myself quite suddenly sick of including loose files in our packaged builds for Siege. Siege Engine being our custom, cross-platform, C++ based game engine using Vulkan (with a very fun name might I add). I was so compelled to do so that I woke up and spent most of my Saturday feverishly tapping out the minimum implementation as example of how such a system would be structured.

Fast forward a day or two and I had implemented a fully operational system for all of our resource types, updated the buildsystem to find and pack all assets on compile, and stripped out all direct file loading from the runtime engine. In that time I’d been happily manipulating pointers and reinterpreting bytes to my heart’s content, but when “they”[1] talk about where there are “dragons”, the “there” is here and the “dragons” are nightmarish memory issues.

While the packing and resource system in Siege is still very much a work in progress I thought it would be of value to document the structure I ended up with, the process it took to get there, and some of the big issues I wrestled with that will keep me up at night.

As with my previous post, I’ll say upfront that this article is not a step by step guide on making an asset packing system in C++. This article is, however, my attempt to document the initial structure, intentions, and issues encountered in the process.

Why bother packing resources?

There’s a few reasons you might come across talking to devs or ones you might find floating around the web (although there are a lot of wrong answers there too). Here are a few reasonable ones I could come up with:

-

File Management & Ease of Use: It may sound like a bit of a non-issue, but for me, the biggest value-add is a tidiness thing. It’s nice to have only a single asset file packaged with your executable. I don’t worry whether a particular asset got deleted and I can just checksum one file. I don’t worry about whether the filesystem is going to give me back the wrong results or hassle me with some permissions shenanigans. I can simply pretend like I’m accessing files via a filepath and if something goes wrong, the pack file must be ill-formed, corrupted, or something in the package is out of date.

-

File Loading Overhead: Opening and reading from files can be costly (for both workload and OS security reasons), so only having to read a single file (or a handful, depending on how you want to chunk it up) into memory can represent a non-trivial performance boost - especially if you can keep often-accessed data mounted through runtime and indexable quickly via a table lookup.

-

Compression: It turns out reducing the surface area on the files has the implicit benefit of shaving off the file metadata, but a far more desirable opportunity exists to explicitly apply some kind of compression across the entire pack file. This file can then be uncompressed on mount once for all resources it contains, which can reduce the final package size significantly.

-

Concealing Assets: Many sources online seem to cite this as public enemy number one thwarted by asset packing, but I’m not entirely convinced of this one myself. First of all, all our assets are publicly available so it doesn’t apply for what we do - I’m not going to care if someone yoinks an asset I made since it was in our public GitHub for the taking anyway. And secondly, if your goal is to prevent users gaining access the the assets, it provides the barest level of security by obfuscation, and would defeat only the most casual hacking and modding attempts (if you even care about that kind of thing).

Fine, how do we do it?

My initial goal was simple: I wanted to write out a plain old data (POD) structure with an arbitrarily long array of entries to a binary file and read it back in. The victim I had in mind for this task: static meshes.

Packer Application & Static Meshes

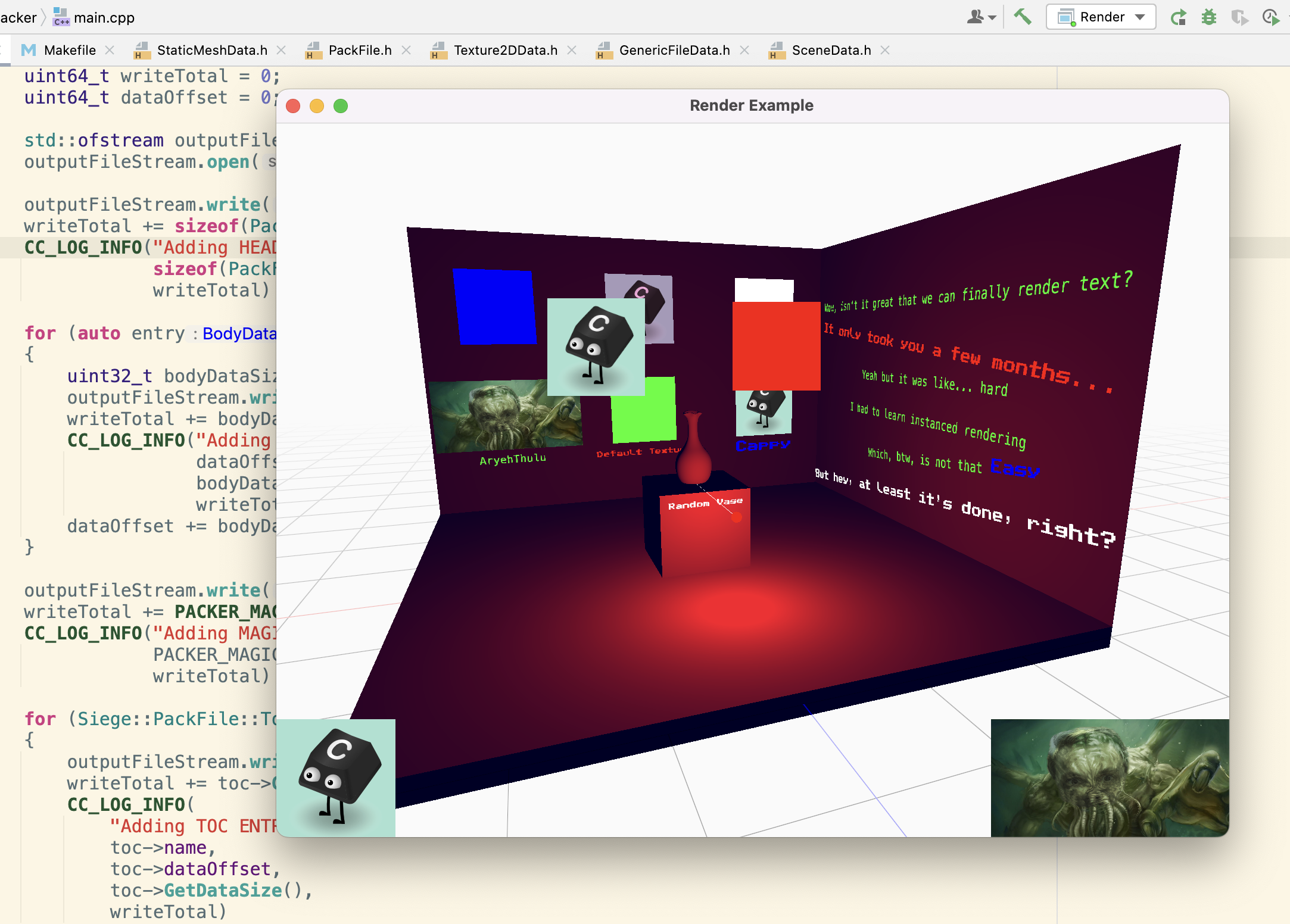

Step 1.A for this operation was going to be adding a new executable to work with, knowing that eventually I would need something to run outside of the runtime engine to perform the packing operations. While I was at it, I felt like I may as well shift the data types into a separate library for inclusion across targets in the build system.

For the Siege buildsystem setup, the structural changes worked out as follows, where the items highlighted in grey were the new additions:

With this done, I had a barebones executable being built and a blank library for my runtime accessible resource data types such as the aforementioned static meshes, which were being loaded from Wavefront (.obj) files using a 3rd party dependency, tinyobjloader. Since only a subset of the Wavefront file data was actually getting fed into the Vulkan mesh rendering pipeline, and knowing we would be support other 3D file formats, I decided to marshall all this information into a new format-agnostic type called StaticMeshData just to add extra work for myself.

The types required, BaseVertex and StaticMeshData, were defined as follows:

struct BaseVertex

{

Vec3 position;

FColour color;

Vec3 normal;

Vec2 uv;

};

struct StaticMeshData

{

uint64_t indicesCount = 0;

uint64_t verticesCount = 0;

char data[];

uint32_t* GetIndices() const

{

return (uint32_t*) data;

}

BaseVertex* GetVertices() const

{

return (BaseVertex*) (data + sizeof(uint32_t) * indicesCount);

}

};The main purpose of this type would be to allow me to write the object directly out to a file from memory as a contiguous block. The dirty trick that allows this to work is the char array on the end labelled data, which essentially points to the first byte in memory following the end of the StaticMeshData object. So how do we allocate for it? Wouldn’t that just point to garbage (or another object) we don’t own? Yes, but not if we bend the rules a bit:

static StaticMeshData* Create(const std::vector<uint32_t>& objIndices, const std::vector<BaseVertex>& objVertices)

{

uint32_t indicesDataSize = sizeof(uint32_t) * objIndices.size();

uint32_t verticesDataSize = sizeof(BaseVertex) * objVertices.size();

uint32_t totalDataSize = sizeof(StaticMeshData) + indicesDataSize + verticesDataSize;

void* mem = malloc(totalDataSize);

StaticMeshData* staticMeshData = new (mem) StaticMeshData();

staticMeshData->indicesCount = objIndices.size();

staticMeshData->verticesCount = objVertices.size();

memcpy(&staticMeshData->data[0], objIndices.data(), indicesDataSize);

memcpy(&staticMeshData->data[0] + indicesDataSize, objVertices.data(), verticesDataSize);

return staticMeshData;

}That’s right. We malloc the total size we need for the object and use placement-new to initialise the object properly (note: because it’s POD we don’t technically need the placement-new but it’s a nice way to get default initialisation on the known members). We’re then free to fill the rest of the memory that follows with the data of the indices and vertices knowing that we own the whole block. It’s important to keep in mind here that calling the object’s destructor will not free the associated memory, so you will need to manually call free on the block once you’re done with it.

At this point we can write out our data to a file and read it back in, noting that if you’re using the C++ standard library’s std::ofstream, you should make sure to pass the std::ios::binary flag when writing to the file in order to prevent it from treating your output as text as so:

std::ofstream outputFileStream;

outputFileStream.open(outputFile, std::ios::out | std::ios::binary);

outputFileStream.write(reinterpret_cast<char*>(&header), sizeof(PackFile::Header));

writeTotal += sizeof(PackFile::Header);

StaticMeshData* staticMeshData = StaticMeshData::Create(objIndices, objVertices);

uint32_t dataSize = StaticMeshData::GetDataSize(data);

outputFileStream.write(reinterpret_cast<char*>(staticMeshData), dataSize);

writeTotal += dataSize;

outputFileStream.close();So why go through with all this tricky memory nonsense? Because you only need to do it on the way out. When the object gets read back in from the pack file, you can just reinterpret_cast the file data to your type and start using it straight away (see below).

StaticMesh::StaticMesh(const char* filePath, Material* material)

{

std::ifstream inputFileStream;

inputFileStream.open(filepath, std::ios::in | std::ios::binary);

inputFileStream.read(reinterpret_cast<char*>(&header), sizeof(PackFile::Header));

body = reinterpret_cast<char*>(malloc(header.bodySize));

inputFileStream.read(body, (uint32_t) header.bodySize);

inputFileStream.close();

StaticMeshData* staticMeshData = reinterpret_cast<StaticMeshData*>(body);

// Filling out the data to submit to the GPU

}After some back and forth I had it all working; I was successfully packing 3D object data to a file and loading it back in for the renderer at runtime!

Table of Contents Authoring & Textures

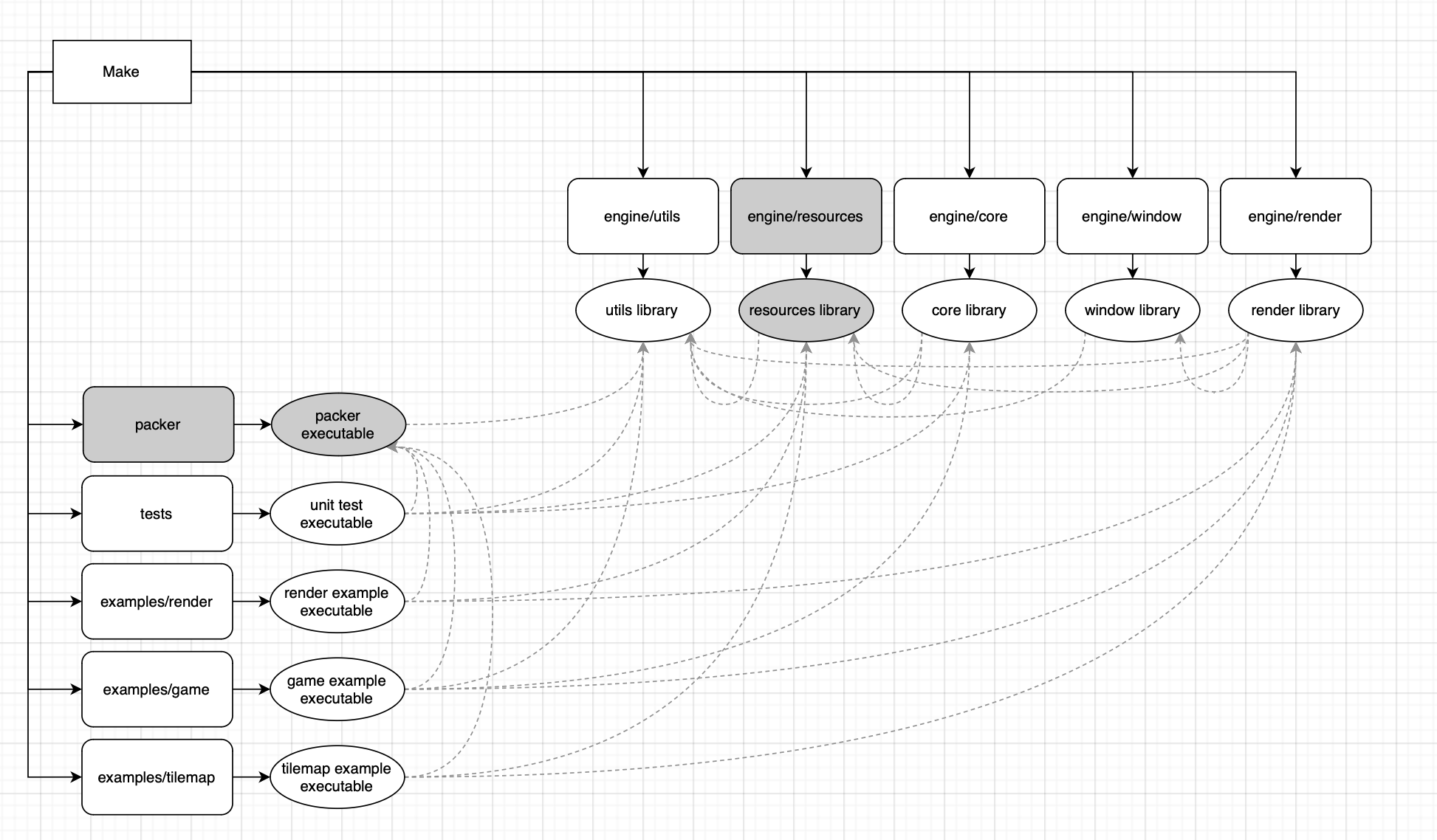

Now that we had our single asset being packed and reloaded, it was time to pack and load multiple assets, and even multiple types of assets from the pack file. Commonly these kinds of files will, like most file types, start with a header section of known structure. Asset pack files will typically then see a table of contents section pointing to data contained in the file body. Another common practice is to prefix the file contents with a magic number that confirms the binary data about to be ingested is indeed the file type we assumed it to be.

At this stage I’d started doing some reading on the topic to see how others would tackle the problem, and stumbled upon this incredibly insightful video of Jonathan Blow, designer of Braid & The Witness, implementing asset packing for his own game engine. Although it seems to all be written in his own procedural programming language, Jai, I managed to take from it a lot of good design decisions.

For one, he unintuitively places his table of contents after the data, which he explains allows the system to append to the pack file without rewriting its contents (if desired). In addition his use of magic numbers was not just limited to the file start, but also included at the table of contents (ToC) offset - a decision that made my debugging experience many times smoother than it would have been otherwise. With all this in mind I devised a structure for my file type (which I would suffix with .pck), as follows:

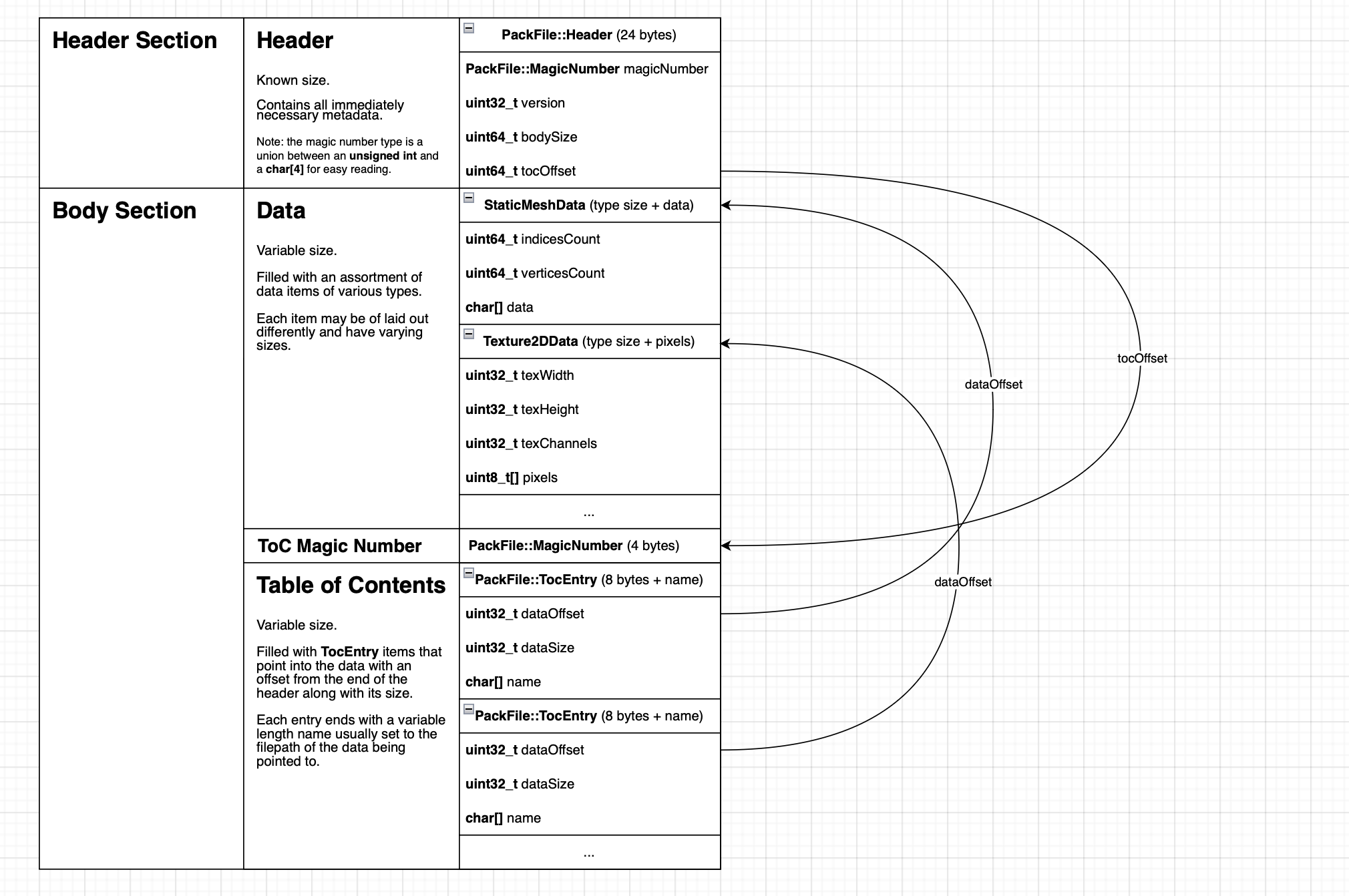

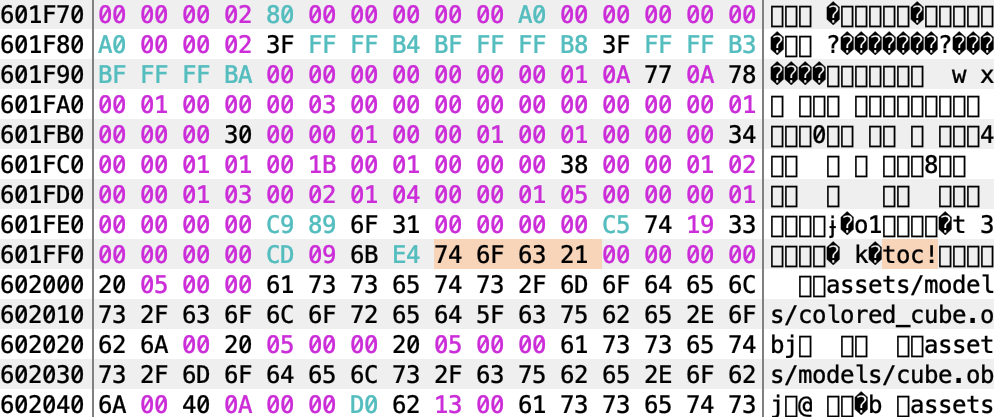

Once this was working for several static meshes, I wanted to add one other data type, and so I went about adding one for Texture2DData. Likewise this was eventually successful, but I cannot stress how valuable having the ToC magic number was when I was debugging; being able to simply search for “toc!” in a file and know exactly what the offset is can be a life-saver:

I will also put in a strong recommendation for pre-calculating your write total, then counting out your actual writes to assert against. You can follow this up with a quick mount and read of the contents before finishing up the packing step, just to make sure the file you just wrote was correctly formed.

Generic File Data for Shaders & Fonts

We’d so far packed our own data types, but the next two biggest line items in our packaged assets would need to be kept whole. Both shaders and fonts would need to have their entire file contents packed and fed into the engine as buffers, meaning we could essentially treat them as the same type, GenericFileData. Turns out this was many times easier to do than the custom structures we were using for the meshes and textures - the more interesting part was finding the correct options in their associated APIs to use.

In the case of the shaders, we were compiling them as a build step to the SPIR-V format as .spv files and handing the binary data to Vulkan’s vkCreateShaderModule as a buffer directly. As for the font data, Freetype ended up requiring the use of their FT_Open_Face function with the FT_OPEN_MEMORY flag set:

Font::Font(const char* filePath)

{

PackFile* packFile = ResourceSystem::GetInstance().GetPackFile();

GenericFileData* fileData = packFile->FindData<GenericFileData>(filePath);

FT_Open_Args args;

args.flags = FT_OPEN_MEMORY;

args.memory_base = reinterpret_cast<const FT_Byte*>(fileData->data);

args.memory_size = FT_Long(fileData->dataSize);

FT_Face fontFace;

CC_ASSERT(!FT_Open_Face(Statics::GetFontLib(), &args, 0, &fontFace), "Failed to load font!")

// Continued font configuration and initialisation

}With almost all our main resource types being part of the pack file, I then updated the Makefiles for each of our executable targets to build and then run the packer application on all files in the staged assets directory.

render-assets:

$(MKDIR) $(call platformpth,$(exampleRenderBuildDir))

$(call COPY,$(binDir)/engine/render/build,$(exampleRenderBuildDir),**)

$(MKDIR) $(call platformpth,$(exampleRenderBuildDir)/assets)

$(call COPY,$(exampleRenderSrcDir)/assets,$(exampleRenderBuildDir)/assets,**)

$(packerApp) $(exampleRenderBuildDir)/app.pck $(exampleRenderBuildDir) $(exampleRenderAssets)

$(RM) $(call platformpth,$(exampleRenderBuildDir)/assets)Looking back, having the pack file automatically regenerating each compile was a huge time saver and something I probably should have added to the buildsystem sooner given that most of the targets I was compiling had a fairly limited number of resources to pack.

Scenes & Entity Files

Now in the home stretch, our last major resource type, and one which I’d been procrastinating, was “entities”. Until a few versions ago, they would have been simple text files, but I’d recently rebuilt the Siege scene files as a folder of entity files, each representing a single entity in the scene. You may be familiar with this strategy, made in the image of Unreal Engine’s OFPA (One File Per-Actor) system, albeit text-based and actually having a human readable file structure. I’m starting to think there might be another blog post in the virtues of the Siege scene system, so I’ll just say that we do things this way because it interacts with Git in such a unique and easy to use manner.

That being said, the bounty of entity files and the lack of a scene file presented a unique opportunity for packing; since we always access all entities in a scene file (essentially a directory suffixed with .scene filed with .entity files) when opening a scene, why not pack them together into a single entry?

For this reason, the packer for the scene file is a little different than the other packer functions, but it is one of the places where the packing system has provided an immediate, objective benefit to the engine.

void* PackSceneFile(const Siege::String& filePath)

{

Siege::String bodyString;

auto appendFile = [&bodyString](const std::filesystem::path& path) {

if (path.extension() != ".entity") return;

bodyString += Siege::FileSystem::Read(path.c_str());

bodyString += '|';

};

bool result = Siege::FileSystem::ForEachFileInDir(filePath, appendFile);

if (!result)

{

CC_LOG_ERROR("Failed to read scene file at path \"{}\"", filePath)

return nullptr;

}

// Allocating and filling out the scene data

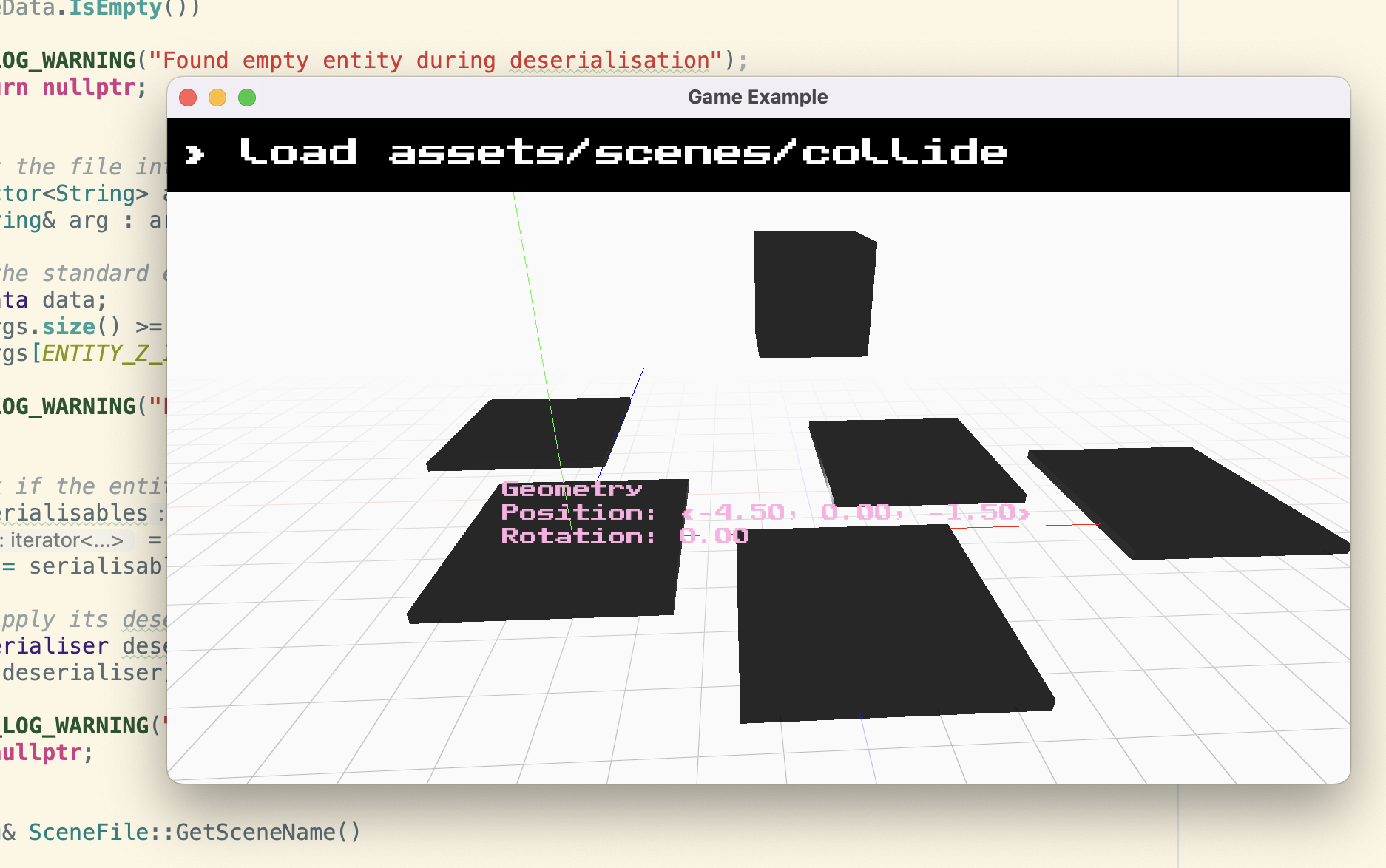

}With all of this done we could now successfully open test scenes in the game example application, fully loaded from the pack file:

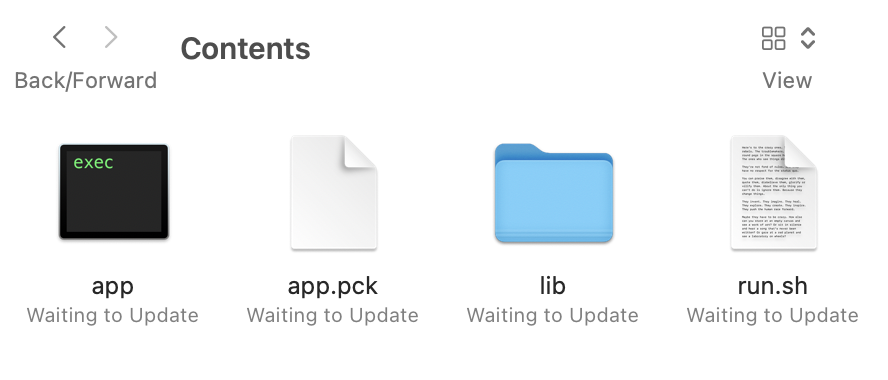

I finally ran the various examples through their packaging steps, and opened up the .app file contents. With only the executable, pack file, and Vulkan dynamic libraries, I found myself pleasantly delighted by the tidiness of it all (run.sh is a script that runs internal to the application on macOS in order to set several environment variables for Vulkan).

You mentioned something about “dragons”?

Dragons? Oh, right, those “dragons”.

So yes, there were a few things I discovered along the way that one should be aware of before the wanton mallocing of memory and pointer casting can continue, as well as some things to keep in mind that’ll keep the conscientious maintainer up at night.

Object Construction & Deallocation

As alluded to in the above section, non-POD objects or those requiring some complex construction cannot be instantiated from a simple cast, and placement-new should be used here instead to provide the new operator with your own memory to allocate to. The catch is that the object’s destructor should be called manually (tptr->~T()), and that you need to manually free the buffer you used.

Since this only happens in the packer, it’s not much of a concern as we can afford to keep allocating until the program ends (for now). Technically we could just leave it be and end the program, but just in case one day we need to continually free up memory while packing, I keep track of all those loose allocations and free them just before exiting as so:

std::vector<void*> dynamicAllocations;

for (auto& file : inputFiles)

{

void* data = nullptr;

// Fill the data pointer with a pack file object using placement-new

TocEntry* tocEntry = TocEntry::Create(file.c_str(), dataSize, bodyDataSize);

// Write the entries to file, do some processing

dynamicAllocations.push_back(data);

dynamicAllocations.push_back(tocEntry);

}

for (void* allocation : dynamicAllocations) free(allocation);Platform Endianness

One phrase in the last section that might have raised some hackles is “write the object directly out to a file from memory”, which may prompt the very valid question about platform endianness. Having a look at a lot of serialisation implementations across Github, you’ll see all sorts of affordances for byte swapping to make their solutions endianness-agnostic.

Looking at the reality of the situation, the engine currently compiles for the three major desktop operating systems from those systems, Windows, macOS, and Linux. These platforms mostly use Intel x86-64, ARM set to little-endian, or Apple Silicon - all of which are little-endian. Even beyond this, you’ll find the current console generation is using little-endian across the board.

As a result, I’ve chosen to just ignore it for now and reap the benefits of not maintaining two code paths or supporting an endian-agnostic file format since it’s not a current concern, nor does it seem to be a concern on the horizon.

Dynamic Dispatch

If you come from an object-oriented background like me you might have thought to reach for that virtual function interface and some inheritance to clean up all that packer code with something like:

struct Packable

{

virtual uint32_t getDataSize() = 0;

};Yeah there’s a reason I have a big switch statement and a bunch of static functions there: the vtable. When you’re writing out your data directly to memory, the last thing you want is to be calculating additional offsets with regard to the vtable pointer, and from one object-oriented addict to another, what problem was this really solving anyway? The packer was always going to have to compile those resource types anyway so why pretend we don’t know what they are? If anything it makes the code more debuggable.

Padding & Alignment

One question that popped into my head while debugging was about what happens when the compiler decides to add its own padding to my structs. If both the types I’m writing from and reading to are padded out in the same way, no problems. If I make sure to pack my structs correctly, fewer problems and less wasted space.

But what if for some reason the packed data and the compiled runtime disagree? Most compilers implement a pragma directive to force packing for a particular alignment, and can be used as so to pack to the byte:

#pragma pack(push, 1)

struct GenericFileData

{

uint32_t dataSize = 0;

char data[];

};

#pragma pack(pop)As I said, ideally you would pack your structs correctly and control any necessary padding yourself, but this is just extra insurance I guess.

The scarier part of this question is, since we’re writing these types of unknown lengths into the binary file contiguously, what does that mean for the structs instantiated from the mounted data? They won’t necessarily be read from addresses aligned to their type, i.e. “misaligned access” which is undefined behaviour. It may not (and probably wont) cause a crash on most modern systems, but it will definitely slow down reads and writes if it crosses a cache line, and I’d like to not have to copy each entry out of the original buffer if possible.

This is a rather worrying prospect and one I do not have an immediate solution for, but I have some ideas involving padding out the pack file as needed to ensure all entries start on a multiple of the word length or so. I’ll definitely be running the application with UBSAN, an undefined behaviour sanitiser for GCC just to see how bad it is in practice.

What’s next?

Despite the concerns raised just above, it all currently works. I’m just in the process of adding some tests for round tripping the data to the tests executable, but I’m happy to continue with this system going forward. Part of the next steps are going to be about analysing the behaviour and identifying issues ahead of time, but I suspect a lot of it is going to come out in the wash with scale.

I neglected to mention that this left the scene system in somewhat of an awkward place, but I do need to fix it up to handle read-only state, and allow the user to point it to read-write loose files while in editor mode. Once that’s done I might also put together a full writeup on the Siege scene system.

If you’re interested in taking a look at Siege Engine’s source code, you can see the repo in action for yourself, or you can take a look at our GitHub to see any of our other open-source projects.

I hope you’ve gotten some value out of this rather lengthy account, whether its ideas for your own packing systems, or satisfying your own sick, morbid curiosity in my memory management folly. Either way, thanks for reading and happy packing!

[1] Big Endian (secretly runs the shadow government)