Setting up your very own Godot build and publishing pipeline with Github Actions

Over the last few months, the Caps team has put together and publicly released a number of build workflow and Godot-centric GitHub Actions. Having recently kicked off a number of new projects utilising them, we thought we might try to share those workflows and our experiences with them for benefit of the gamedev community.

This article is not an introduction to using GitHub Actions. GitHub provides many of those themselves that are of far higher quality and more up-to-date. Additionally Caps Collective is an open-source, indie team of only a handful of devs, and should be taken into account when evaluating the suitability of technologies and strategies described here to your own projects.

This article is, however, a beginner-friendly explanation and rationale for the GitHub Actions workflows we authored, and how they all tie together in our build and publishing pipeline.

Why did we do this?

As the Caps team rolled off Fantasy Town Regional Manager (FTRM) and looked toward new endeavours, we reflected heavily on the learnings and pain points we encountered in the development and ongoing support afforded to our previous title:

-

Code review is good

While utilising pull requests and reviewing every change that went into the codebase slowed us down to some extent, it also provided the whole team with the opportunity to read, verify, and manage changes to the project. We came out of FTRM recognising the dividends it paid to do code review and strictly version our changes. -

Generating and publishing builds locally is bad

While there was originally a plan to automate our build and publishing pipeline on FTRM, it didn’t materialise as (among many other issues) Unity broke their CI support across several versions of the engine over licence verification problems. As a result, we had to build locally on our dev machines and then upload each build individually to each service. I shouldn’t need to describe to you how much strife this caused between platforms breakages, environment errors, and just plain human error.

With this in mind, and knowing that we would continue to operate as open-source, GitHub Actions was a good match for us, being free, cloud-based, and transparent.

We had agreed by the end of development (late 2021) that we had zero intention to build our next title with Unity, and while we hadn’t fully settled on working with Godot, it came with one very attractive property: it’s small. It’s so small and lightweight in fact that we would be able to download the entire engine in a runner to a clean environment for testing and build.

From this, we started to imagine the automation possibilities; version checking and tagging, dev and release build generation, smoketesting, automated validation, and distribution platform upload were tantalising propositions to say the least!

We were thrilled with the sheer number of mundane things we could finally leave to a machine while we could simply focus on actually making a game.

What did we get?

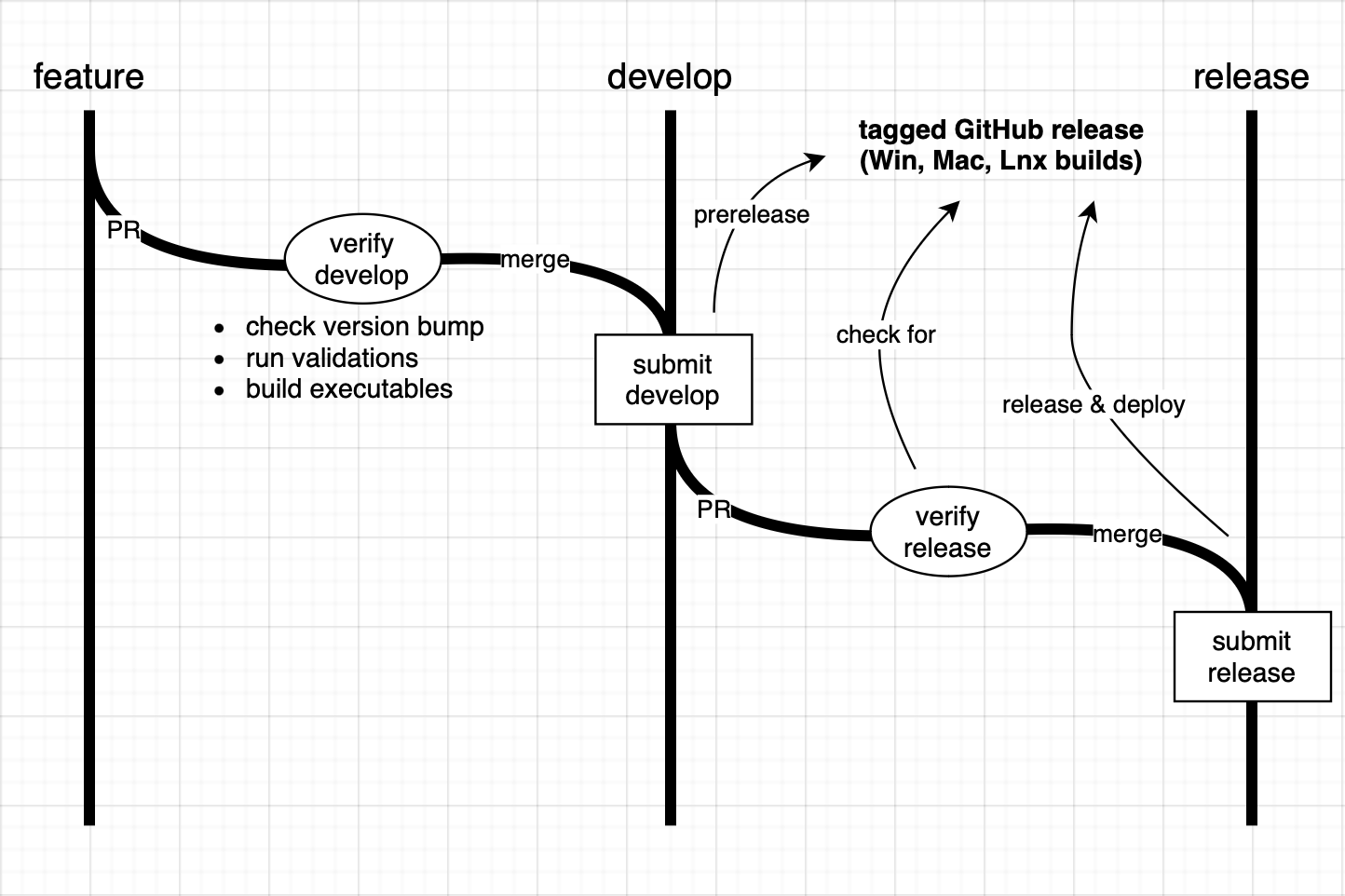

The pipeline we ended up with was composed of two broad phases, governing the merging of changes into develop and release branches respectively. These two phases are then split up into two lifetime event steps; pre-merge validation, and post-merge housekeeping, such as tagging and distilling builds.

A key distinction in setup between the lifetime events is that the pre-merge validation step is run when the code is sent for PR, and then rerun every time code on that branch changes until merge, whereas the post-merge step could only run once, on merge, as they mutated the state of the repository. As such, a successful pass of the pre-merge step needed to be exceptionally confident in the post-merge step not failing.

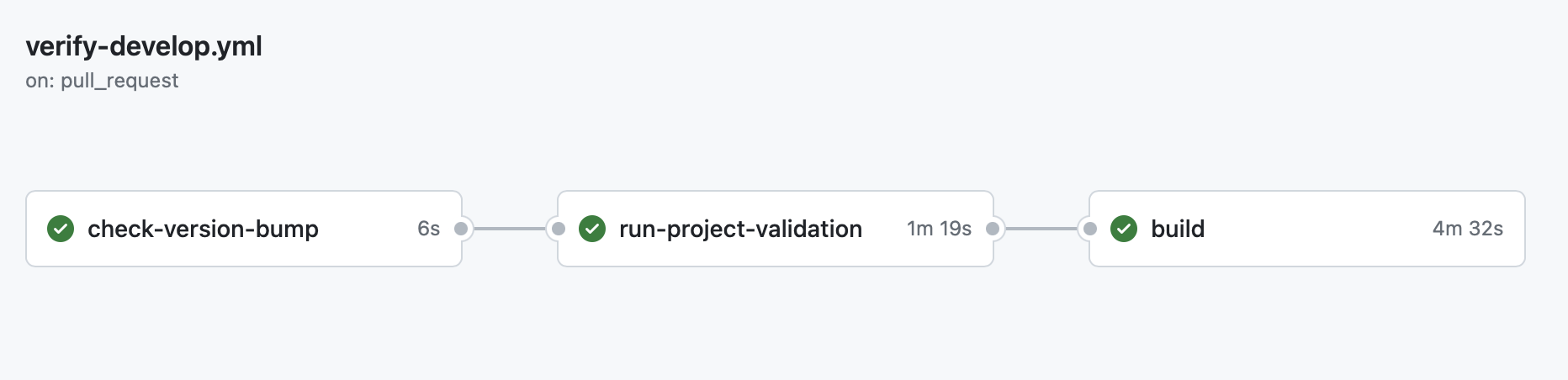

The pre-merge step on develop, otherwise referred to as verify-develop, provided the following (in the below order), aborting the runner if any job failed:

- Semantic version checking: the runner would verify that the build version had been bumped in project settings

- Project validation check: this would run all project defined validations setup by the team, such as resource import settings, data schema compliance, and gameplay level integration tests

- Project build across platforms: all target platforms would be built to, each being checked for warnings or missing files, and then uploaded to GitHub’s artifact storage system for manual download and testing

As stated above, verify-develop, would be run every time the PR’d branch changed until review and merge, at which point, the post-merge step, submit-develop would be run, providing the following:

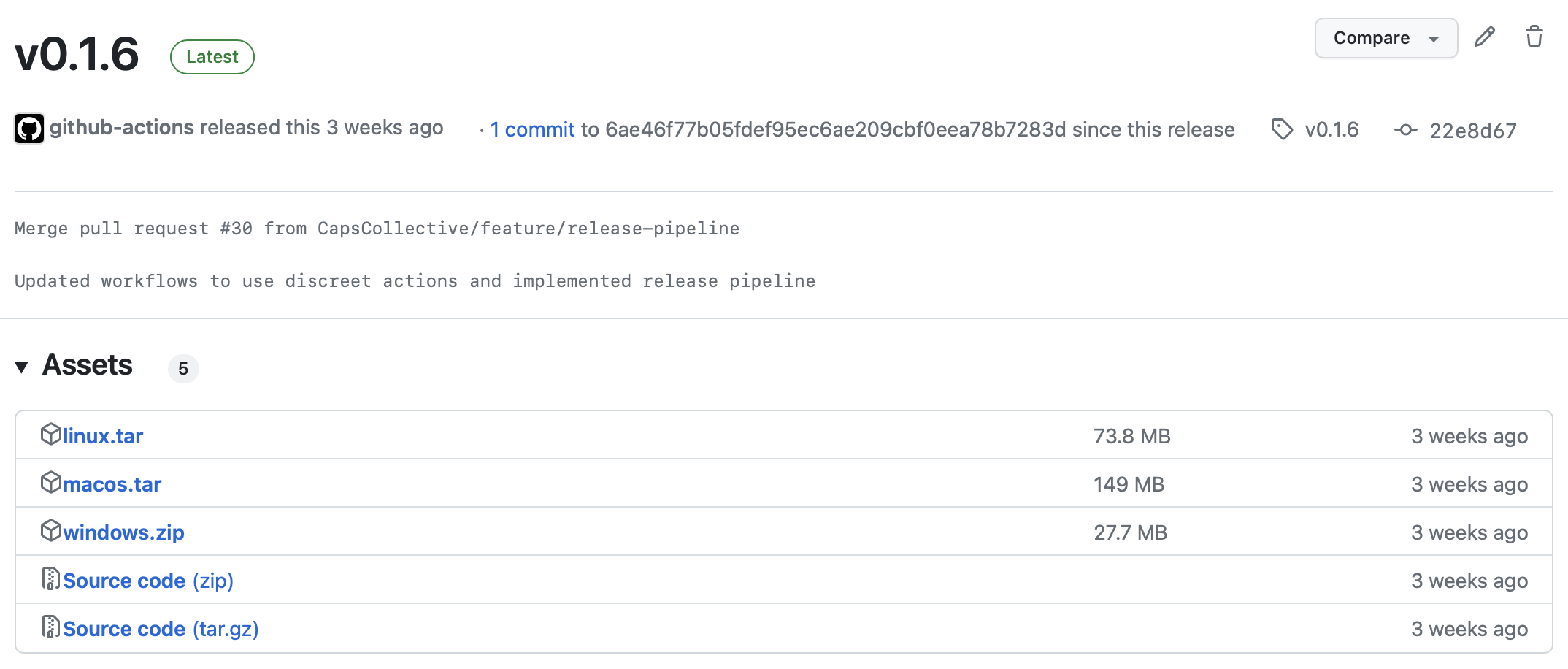

- Project build across platforms: the runner would generate and distill the build for each target platform

- Release tagging: the commit for the build would be tagged at the point of build for future reference

- Release posting: the generated builds would be uploaded next to a snapshot of the source code for future reference

The release branch version of this process piggybacked off the work already done where verify-release would simply make sure the PR’d commit matched a release commit exactly before merge. submit-release then pulled the distilled release generated by submit-develop, deployed it to each of our distribution platforms (Steam, itch.io, etc.), and then updated its release status for future reference.

Note that we do not run build again, not just to avoid extra work, but also because a great deal of time can pass between a build going from develop to release, introducing a higher chance that some external factor could change and break the build. We’d much rather upload the build we generated during the original PR that we have on file, and can test manually beforehand.

While the two phases described above might imply that all builds go through these steps, the workflow for the pipeline is slightly less rigid. All changes to the project must go through develop in lock-step, however, only some tagged versions are explicitly sent through the release pipeline (with the changes they sit on top of coming along for the ride). For example, build versions 0.1.5 through 0.1.8 might only ever exist as prerelease versions until 0.1.9 is sent to release and deployed to Steam and itch.io. This allows us to tag and talk about our incremental changes in version numbers without sending every iteration of the work out for alpha branch testing (we do not immediately send our deployed builds out to players for obvious reasons).

How did we do it?

So let’s get down to brass tacks here, how did this dream pipeline actually work? Well, it just took a lot of GitHub Actions scripting - fiddling with YML files and the like.

I’ll post a snapshot of each of the workflow files from one of our current projects here for reference, but I’ll only comment on the interesting bits and leave the rest of their interpretation as homework for the reader.

Below is the workflow for verify-develop. As you can see, each job uses the needs: property to enforce a dependency on the previous job, aborting the runner if any job fails.

Take note of the calls to open the Godot editor in headless mode and immediately quit - this is to force the engine’s class DB to regenerate before running any operations as this information is usually cached on your local machine and ignored from the repo. Failing to do so may result in GDScript missing type information while running command line scripts using custom types, or builds generating a large quantity of warnings and errors on first run.

name: 'Verify Develop'

on:

pull_request:

branches: [ 'develop' ]

env:

GODOT_VERSION: 4.2

VERSION_FILE: project.godot

VERSION_REGEX: config\/version=\"\K[0-9.\-A-z]*

jobs:

check-version-bump:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Checkout current branch

uses: actions/checkout@v3

with:

ref: ${{ github.base_ref }}

- name: Extract old version string

uses: CapsCollective/version-actions/extract-version@v1.0

with:

version-file: ${{ env.VERSION_FILE }}

version-regex: ${{ env.VERSION_REGEX }}

id: extract-version-old

- name: Checkout current branch

uses: actions/checkout@v3

- name: Extract new version string

uses: CapsCollective/version-actions/extract-version@v1.0

with:

version-file: ${{ env.VERSION_FILE }}

version-regex: ${{ env.VERSION_REGEX }}

id: extract-version-new

- name: Check semantic version bump

uses: CapsCollective/version-actions/check-version-bump@v1.0

with:

new-version: ${{ steps.extract-version-new.outputs.version-string }}

old-version: ${{ steps.extract-version-old.outputs.version-string }}

run-project-validation:

needs: check-version-bump

runs-on: macos-latest

steps:

- name: Checkout current branch

uses: actions/checkout@v3

- name: Install Godot

uses: CapsCollective/godot-actions/install-godot@v1.0

with:

godot-version: ${{ env.GODOT_VERSION }}

id: install-godot

- name: Open Godot editor for reimport

run: ${{ steps.install-godot.outputs.godot-executable }} --editor --headless --quit || true

- name: Run project validations

run: ${{ steps.install-godot.outputs.godot-executable }} --script scripts/run_validations.gd --headless

build:

needs: run-project-validation

runs-on: macos-latest

steps:

- name: Checkout current branch

uses: actions/checkout@v3

- name: Install Godot

uses: CapsCollective/godot-actions/install-godot@v1.0

with:

godot-version: ${{ env.GODOT_VERSION }}

install-templates: true

id: install-godot

- name: Open Godot editor for reimport

run: ${{ steps.install-godot.outputs.godot-executable }} --editor --headless --quit || true

- name: Build and upload artifacts for all platforms

uses: CapsCollective/godot-actions/build-godot@v1.0

with:

godot-executable: ${{ steps.install-godot.outputs.godot-executable }}You may have noticed at this point that the whole system is largely reliant on our publicly available CapsCollective/version-actions and CapsCollective/godot-actions. They are GitHub Actions which encapsulate some of our most common operations such as extracting the project version from a file and checking semantic versions, installing a particular version of the engine with export templates, building the project, and even uploading builds to GitHub’s artifact storage.

Below you’ll see submit-develop, which tags the commit, and uploads artifacts to GitHub. When referring to commit hashes/branch names, github.sha is the commit hash of the commit that triggered the workflow, and github.base-ref is the target branch of the PR. Keep in mind that default environment variables in GitHub Actions workflows are contextual and can change meanings or even remain undefined depending on the workflow type.

name: 'Submit Develop'

on:

push:

branches: [ 'develop' ]

env:

GODOT_VERSION: 4.2

VERSION_FILE: project.godot

VERSION_REGEX: config\/version=\"\K[0-9.\-A-z]*

jobs:

build:

runs-on: macos-latest

steps:

- name: Checkout current branch

uses: actions/checkout@v3

- name: Install Godot

uses: CapsCollective/godot-actions/install-godot@v1.0

with:

godot-version: ${{ env.GODOT_VERSION }}

install-templates: true

id: install-godot

- name: Open Godot editor for reimport

run: ${{ steps.install-godot.outputs.godot-executable }} --editor --headless --quit || true

- name: Build and upload artifacts for all platforms

uses: CapsCollective/godot-actions/build-godot@v1.0

with:

godot-executable: ${{ steps.install-godot.outputs.godot-executable }}

generate-release:

needs: build

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Checkout current branch

uses: actions/checkout@v3

- name: Extract version

uses: CapsCollective/version-actions/extract-version@v1.0

with:

version-file: ${{ env.VERSION_FILE }}

version-regex: ${{ env.VERSION_REGEX }}

id: extract-version

- name: Download macOS artifact

uses: actions/download-artifact@v3

with:

name: macos

path: artifacts/macos

- name: Download Windows artifact

uses: actions/download-artifact@v3

with:

name: windows

path: artifacts/windows

- name: Download Linux artifact

uses: actions/download-artifact@v3

with:

name: linux

path: artifacts/linux

- name: Tag and upload artifacts to release

uses: ncipollo/release-action@v1

with:

tag: ${{ steps.extract-version.outputs.version-string }}

commit: ${{ github.sha }}

allowUpdates: false

artifactErrorsFailBuild: true

prerelease: true

artifacts: artifacts/*/*Additionally you may see that our build steps all run using the macOS runner, whereas all our other operation use Ubuntu. This is because we’ve found across our previous experience in Godot, Unity, and Unreal, that building through macOS is usually the most stable and surefire way to go. It typically supports Windows and Linux builds reasonably well, and avoids any nasty issues with adhoc permissions and compilation level signing requirements Apple have for their ecosystem.

verify-release, as you can see is rather short and simple in that it’s just a single job that checks the tag version of the PR’s head commit exists as a GitHub release, and then double checks that version matches what the checked out project file has.

name: 'Verify Release'

on:

pull_request:

branches: [ 'release' ]

env:

VERSION_FILE: project.godot

VERSION_REGEX: config\/version=\"\K[0-9.\-A-z]*

jobs:

check-release-validity:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Checkout current branch

uses: actions/checkout@v3

- name: Extract version

uses: CapsCollective/version-actions/extract-version@v1.0

with:

version-file: ${{ env.VERSION_FILE }}

version-regex: ${{ env.VERSION_REGEX }}

id: extract-version

- name: Check that a release exists for the HEAD commit

uses: cardinalby/git-get-release-action@v1

env:

GITHUB_TOKEN: ${{ github.token }}

with:

commitSha: ${{ github.event.pull_request.head.sha }}

id: check-release

- name: Check that the release tag matches the version string

run: |

[ ${{ steps.extract-version.outputs.version-string }} = ${{ steps.check-release.outputs.tag_name }} ]It’s important to call attention to our usage of github.sha vs github.event.pull_request.head.sha when referring to commit hashes, as previously stated, GitHub Actions treats variables differently depending on whether the calling workflow is triggered on pull_request, or push. In a pull_request context, one must use github.event.pull_request.head.sha to get the last commit to the head branch of the PR as opposed to the commit hash of the last merge commit of the PR’d branch (you can read more about this absurdity here).

Finally we have the workflow file for submit-release, which downloads the specified release, and performs platform deployment to itch.io (Steam has been left out on this particular project until such time that we pay for a new app-id). All our API keys are stored with GitHub’s “secret” environment variables, which allows us to write them into our workflows, but are stricken from the results of any runner output.

name: 'Submit Release'

on:

push:

branches: [ 'release' ]

env:

VERSION_FILE: project.godot

VERSION_REGEX: config\/version=\"\K[0-9.\-A-z]*

jobs:

deploy-release:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Checkout current branch

uses: actions/checkout@v3

- name: Extract version

uses: CapsCollective/version-actions/extract-version@v1.0

with:

version-file: ${{ env.VERSION_FILE }}

version-regex: ${{ env.VERSION_REGEX }}

id: extract-version

- name: Fetch macOS build

uses: dsaltares/fetch-gh-release-asset@1.1.1

with:

version: tags/${{ steps.extract-version.outputs.version-string }}

file: macos.tar

target: artifacts/macos.tar

- name: Decompress macOS build

run: |

mkdir -p build/macos

tar -xvf artifacts/macos.tar -C ./build/macos

- name: Fetch Windows build

uses: dsaltares/fetch-gh-release-asset@1.1.1

with:

version: tags/${{ steps.extract-version.outputs.version-string }}

file: windows.zip

target: artifacts/windows.zip

- name: Decompress Windows build

run: |

mkdir -p build/windows

unzip artifacts/windows.zip -d ./build/windows

- name: Fetch Linux build

uses: dsaltares/fetch-gh-release-asset@1.1.1

with:

version: tags/${{ steps.extract-version.outputs.version-string }}

file: linux.tar

target: artifacts/linux.tar

- name: Decompress Linux build

run: |

mkdir -p build/linux

tar -xvf artifacts/linux.tar -C ./build/linux

- name: Deploy macOS build to itch.io

uses: KikimoraGames/itch-publish@v0.0.3

with:

butlerApiKey: ${{ secrets.BUTLER_API_KEY }}

itchUsername: ${{ vars.ITCH_USERNAME }}

itchGameId: ${{ vars.ITCH_GAME_ID }}

gameData: ./build/macos

buildChannel: macos-release

buildNumber: ${{ steps.extract-version.outputs.version-number }}

- name: Deploy Windows build to itch.io

uses: KikimoraGames/itch-publish@v0.0.3

with:

butlerApiKey: ${{ secrets.BUTLER_API_KEY }}

itchUsername: ${{ vars.ITCH_USERNAME }}

itchGameId: ${{ vars.ITCH_GAME_ID }}

gameData: ./build/windows

buildChannel: windows-release

buildNumber: ${{ steps.extract-version.outputs.version-number }}

- name: Deploy Linux build to itch.io

uses: KikimoraGames/itch-publish@v0.0.3

with:

butlerApiKey: ${{ secrets.BUTLER_API_KEY }}

itchUsername: ${{ vars.ITCH_USERNAME }}

itchGameId: ${{ vars.ITCH_GAME_ID }}

gameData: ./build/linux

buildChannel: linux-release

buildNumber: ${{ steps.extract-version.outputs.version-number }}

- name: Update release status

uses: ncipollo/release-action@v1

with:

tag: ${{ steps.extract-version.outputs.version-string }}

commit: ${{ github.sha }}

allowUpdates: true

updateOnlyUnreleased: true

prerelease: falseYou’ll see that we tar files for macOS and Linux, but zip those for Windows. The reason for this is that GitHub tar preserves permissions on files, and prevents end users from having to chmod the executable on download. We wanted to similarly pack Windows, but realised it did not come by default with an archiving utility capable of handling tar file, so we instead used the zip format purely for ergonomic reasons.

What’s the catch?

Ok, you got me, this pipeline isn’t all sunshine and rainbows, so here are the pain points:

- You cannot run workflows locally (without a lot of pain and caveats), so to tune or debug anything, you just need to keep force-pushing commits to a PR as you especially cannot inspect the environment post-run so

echobecomes your best friend here real quick! - It’s not a real, continuous environment? Each job is run on a separate VM, so environments will potentially need to be set up multiple times within the same workflow, and job steps do not share environment variables. You can see the amount of GitHub Actions environment variables being written to across the files and it can be a bit of hassle when all you really needed was to pass a string from one step to the next.

- Lots of runner weirdness abound! You find small, weird behaviours all the time you have to work around like particular version of preinstalled software in the image can’t be replaced, or particular commands work slightly differently on a real machine, or anything I’ve noted in the above sections about the contextual workflow variables (and avoid using Windows runners wherever possible because they take some serious creative licence with simple Batch and PowerShell commands!).

Altogether we have these few minor gripes here and there, but have found them to be mostly manageable given the total value we’ve gotten with the system thus far.

What’s next?

Well honestly, we don’t need our CI/CD system to be doing much more at the moment, so we’re mostly just working on games and tightening it up as we go to further reduce room for error, especially around centralising configurations. We’re also moving GitHub Actions workflow scripts out to GDScript, so that in the event that we switch CI/CD platforms, we wouldn’t be starting from nothing.

The next step for us really would be to support native plugin and custom engine builds, which would require runners doing builds on all three platforms separately. So far we haven’t needed to do that with our current Godot 4 projects as we have with the build pipeline for Siege Engine, our custom, Vulkan/C++ game engine, but we’ll burn that bridge when we come to it.

Until then, thank you for reading, and I hope this article has been useful to you in illuminating some of the darker corners of our build and publishing pipeline and perhaps it may have given you some ideas for automation on your own projects (or at the very least entertained you with a full account of our Rube Goldberg machine tier automation pipeline).